Cerne Giant mystery solved?

The Dorset chalk figure known as the Cerne Giant was most probably created in the early Middle Ages, according to recent dating work. Contextualising the archaeological work by the National Trust, authors of a new study say the figure was cut in the ninth or early tenth century when there was much interest in the Greek hero Hercules. In their paper in the journal Speculum, Thomas Morcom and Helen Gittos explain at length when and why the figure was cut in the image of Hercules and why it was done in this West Saxon landscape.

By PeteHarlow, CC BY-SA 3.0, Link

The Cerne Giant, located outside the village of Cerne Abbas, is approximately 55 metres long and 51 metres wide. The hill on which it was carved also features an Iron Age earthwork, which the authors say, has never been investigated archaeologically but which was considered important enough to give the hill its name until recently.

Previous attempts to date the giant placed its creation either sometime in prehistory or in the early modern period. Using a technique called optically stimulated luminescence, researchers for the National Trust theorised that the hillside monument was actually constructed in the period between 700 and 1100 AD, and potentially used as a mustering site for West Saxon armies.

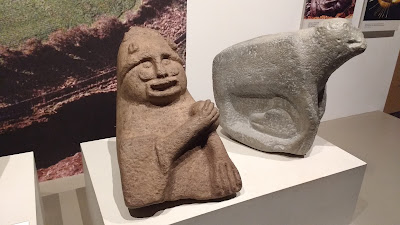

Morcom and Gittos describe the early medieval date as fitting with the form of the giant's face. The distinctive tear-drop shape is akin to other human faces in Anglo-Saxon art, such as the ones on the Sutton Hoo scepter, the Finglesham buckle, and figurines from Kent and East Anglia.

Another popular theory regarding the inspiration for the giant was its basis on a Saint Eadwold. The authors propose that the residents of a Benedictine monastery, built in Cerne in the late tenth century, actively propagated this idea, redirecting interest in the giant away from Greek affiliations and towards Christian ones.

One final persona bestowed upon the giant was that of a pagan god called Helith. The authors explain that this identification was a mistaken one, the result of a misreading, in the thirteenth century, of an account of the giant written in Latin.

Identification with the god Hercules is nothing new as the authors point out: "The resemblance has been recognized since at least the mid-eighteenth century, when the giant was identified as “our High Admiral Hercules” by William Stukeley. Stuart Piggott in the 1930s made the case more fully, and the giant is now accepted as an image of Hercules in the The club is the clue. Hercules was one of the most frequently depicted figures in the classical world, and his distinctively knotted club acted as an identificatory label..."

The new findings concerning the Cerne Giant’s age and history make greater sense of this string of theories regarding its identity. Ultimately, as the authors write, this complicated biography is all “part of the history of the giant and what continues to attract so many people to him.”

Read the very accessible paper in Speculum. The University of Chicago Press issued a press release to summarise its findings.

Help to support my blog by becoming a Shutterstock contributor.

Comments

Post a Comment